Kona is rich in history. John Heckathorn for

Hawaii Magazine on the history of the Kona Coast. Join us on a

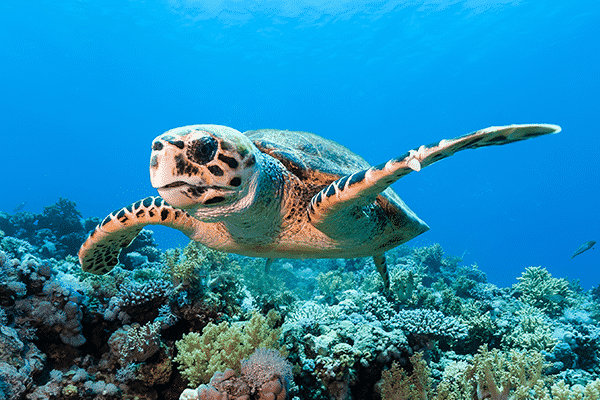

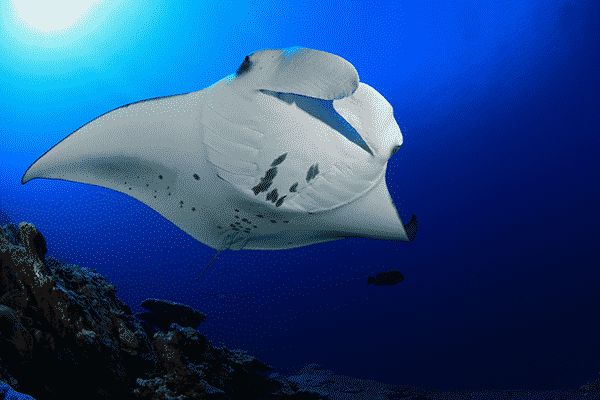

snorkel or manta ray tour to see the mystical creatures and the beauty of the Kona Coast.

Everywhere you turn on the ruggedly beautiful Kona Coast, you encounter traces of the past.

Everywhere you turn on the Kona Coast, you encounter traces of the past.

On this lava-filled leeward coast of Hawaii’s Big Island, Capt. James Cook died, in a skirmish over a rowboat.

Only a few miles from where Cook perished, Kamehameha the Great fought his first major battle.

After nearly 30 years of struggle to unify the kingdom, Kamehameha enjoyed his final years in a grass

hale (house) on the shores of Kailua Bay.

In the same spot, six months after Kamehameha’s death, his heir, Liholiho, and his favorite wife, Queen Regent Kaahumanu, abolished the

kapu system, the religious and social laws that governed traditional Hawaiian society.

A year later, into this same harbor, and into the cultural vacuum created by the breaking of the kapu, sailed the brig Thetis with the first New England missionaries.

Kona was the tumultuous center of the Hawaiian kingdom, long before the capital moved to Honolulu. To find traces of the past in Kona, all you have to do is look.

On a morning walk around our home base, the Sheraton Keauhou Bay Resort, we happened upon ruins of Hawaiian dwellings and

heiau (temples).

Just five minutes up the coast, at the Keauhou Beach Resort, we found ourselves up on the hotel’s roof, from which we could spot not one, but several heiau, the concentration of ancient temples a reminder that this was an important place in traditional Hawaiian culture.

Two of these heiau—Hapaialii and Keeku—rise imposingly at the water’s edge, massive constructions of lava rock.

Over the centuries, many similar Hawaiian heiau have been destroyed by development, leaving bare stone outlines. Here, however, the major landowner, Kamehameha Investments, is actively restoring them—as accurately as possible, with a team of archaeologists, cultural experts and experts in

uhau humu pohaku, the Hawaiian art of dry-stack masonry.

When the heiau was reconstructed to precise measurements, the builders realized that, if you stood on the observation stone during the winter solstice, the sun set precisely behind a rock at one corner. During the summer solstice, it set precisely above the other corner.

Because Hapaialii was flat, it’s thought to be used for public prayer. Its walled companion, Keeku heiau, had a grimmer purpose. It was a

luakini, a place of human sacrifice. Behind the lava-rock walls, a 16th-century Maui chief, defeated after a bitter battle, was bloodily sacrificed. His two dogs, one white, one black, died in grief at their master’s fate. They are buried in the corners of the heiau, as spiritual guardians, and their story told in petroglyphs visible at low tide.

There are 37 heiau, some mere traces, and dozens of other historic sites, in the Kona coast’s Keauhou region alone. For a survey of them and an update on the restorations, you can stop by the free Heritage Center Museum in the Keauhou Shopping Center.

Keauhou is the old name for an ancient land division called an

ahupuaa (which stretched from the mountains to the sea). You can see the boundaries of the old ahupuaa, now marked with carved wooden posts, as you make the short drive from Keauhou to the town of Kailua-Kona—or, as it now refers to itself after considerable sprucing up, Historic Kailua Village.

The most historic buildings in Historic Kailua Village sit across the street from each other: Mokuaikaua Church and Hulihee Palace. Mokuaikaua was the first Christian church in the Islands—and remains a dark and dusty monument to the first missionaries who sailed into Kailua Bay in 1820 on the 85-foot Thetis, after an arduous, 163-day voyage from Boston.

The 17 members of the missionary company brought New England ways with them, and boasted that the graceful, 112-foot spire of Mokuaikaua, once the dominant landmark on this coast, was “almost a facsimile of some that anciently stood in the commons of many a New England village.”

The missionaries left an indelible mark on the Islands. The missionary company on the Thetis was led by Rev. Asa Thurston. His grandson, Lorrin, would become a prime mover in overthrowing the Hawaiian monarchy and annexing Hawaii to the United States.

Before that happened, the Hawaiian monarchs enjoyed themselves in Hulihee Palace, just across the street. The palace is only a year newer than Mokuaikaua, built in 1838, but, in sharp contrast to the old church, it has been restored to sparkling condition, with repairs necessitated by damage from the 2006 earthquake.

Built by John Kuakini, the governor of the Big Island, the palace eventually passed down to Princess Ruth Keelikolani, who slept in a thatched hale on the grounds, though the palace itself saw the slumbers of many visiting royals.

Ruth was the richest woman of her time. She was also one of the largest, weighing 440 pounds.

The treasures on display include Kamehameha I’s personal war spears, as oversize as the man himself; Princess Kapiolani’s

koa traveling trunk, lined with lead against the rigors of sea travel; and an ornately carved koa wardrobe, a testament to Hawaiian woodworking skill that won a silver medal in the Paris Exhibition of 1889.

The wardrobe, like many of the other Victorian touches, including the 22-karat-gold moldings on the walls, are all works commissioned by King David Kalakaua, who inherited the palace in the 1880s.

There’s plenty of history to learn in Kona, and it did not end with the passing of the Kamehameha dynasty. As the 19th century wore on, Kona’s story became the story of many nationalities.

Among them was the Englishman, Henry Nicholas Greenwell, whose attempt to join the California Gold Rush went awry, but who luckily ended up on this coast in 1850, just as foreigners were allowed to purchase land.

Greenwell went on to become customs collector, postmaster, school inspector, storekeeper, rancher and entrepreneur. His headquarters, just south of Kailua-Kona, have become the center for the Kona Historical Society, which now boasts 1,000 members nationwide.

The society doesn’t want dusty museums. It wants history to live.

For instance, in Greenwell’s store, visitors interact with a costumed storekeeper and are given a shopping list that might have belonged to, say, a 19th-century Portuguese dairy farmer. The storekeeper finds whatever that dairy farmer might have needed, from a wool shirt to a new butter churn.

The choice of a Portuguese dairy farmer is not random. The Portuguese arrived in Kona in the 1870s, bringing with them not only expertise in managing dairies, but also their baking traditions.

On Thursdays, you can relive that tradition. A young couple, Lewis and Carla Drexler, light up a

kiawe fire in the society’s forno, an 8-foot-diameter stone oven like those used by the Portuguese immigrants. When the oven heats up, they shovel the coals out.

The stones hold heat long enough to bake 96 golden loaves of Portuguese sweet bread. Lewis has to use a metal paddle with a 10-foot handle to get loaves in and out of the oven. “It’s 450 degrees,” he says. “I’ve learned not to stick my head in to see how things are going.”

Visitors are welcome to help prepare the loaves—and sample some finished sweetbread. Carla sells the rest up by the highway, where the loaves are gone in two hours. Baked the old-fashioned way, each loaf is a tribute to the hard-working Portuguese women who brought to Hawaii one of its favorite foods. (See this article for a recipe for Portuguese sweet bread you can make yourself, without a stone oven.)

After the Portuguese, many Japanese arrived in the Islands to work the growing sugar plantations. Their contracts up, some came to Kona for a more independent life. One of them, Daisuku Uchida, began a small coffee farm in 1913.

His son, Masao, farmed that land as well, until 1997. The Kona Historical Society has preserved the farm, but not as a museum. The farm is still alive, producing coffee.

Things are so lively when we arrive, it looks like the farmhouse is on fire.

“Don’t worry,” says Pauline Nishida-Miller. “I’m just cooking rice.”

Nishida-Miller—wearing an apron made of a recycled rice sack and a vintage dress her grandmother might have worn—is laboring in the farm house kitchen over a wood fire. There’s no chimney here, the smoke just pours out of an opening above the stove.

The wooden house is simple, tin roof, wood walls with gaps that let the sunshine and weather in. “Actually, it’s a better house than the one I grew up in, just a few miles away,” says Nishida-Miller.

Using sustainable resources, recycling, living off the grid—all these are trendy again. As Nishida-Miller demonstrates, the Uchida Farm was doing all those things back when they were necessities. The wood for the fire is collected from the farm’s coffee trees. The vegetables in the simple lunch are grown in the farm’s garden. Even the filter on the faucet is a Bull Durham sack like the one in which Daisuku Uchida used to buy his tobacco.

“They recycled everything,” says Nishida-Miller. “They had to. This was nearly a cash-less society.”

On the sloping lands of the farm, another costumed performer, Yolanda Olson, shows how to pick ripe coffee beans off the trees. (Most Kona coffee grown on hillsides is still handpicked).

A farmer could get more money from processed than raw beans, so the ever industrious Uchidas built their own coffee mill, powered by a three-horsepower two-cycle John Deere engine. Olson shows how it’s done. She grinds the red pulp off the coffee cherries, washes the beans by soaking them in water, and then dries them in the sun on a flat roof called a hoshida, raking them so they dry evenly. The dried beans—called parchment—are then bagged and carried by donkey to the wholesaler.

The farm still has a donkey, Charlie, who seems content to munch grass around the macadamia nut trees rather than do any work today.

No history book can bring life to a coffee farm like this one. The Kona Historical Society is raising money to create a historic ranch on the same model. Kona has a long ranching tradition, and it, too, needs a dose of living history.

History seems alive, too, at one of the best-known ancient sites on this coast, Puuhonua o Honaunau, the City of Refuge, now a National Historical Park.

These 420 acres of preserved Hawaiian past come with a new, high-tech flourish. At Puuhonua o Honaunau, you can call (808) 217-9279 and get an audio tour of the park on your cell phone. (You pay for cell minutes, but otherwise, like the park, it’s free.) There’s also a virtual tour where you can explore the park on your computer.

The park contains both a royal compound and a walled city of refuge, the puuhonua, where breakers of kapu and others in trouble could take refuge behind the 17-foot-thick, 10-foot-high lava wall. The refuge was made even more sacred by the remains of 23 high chiefs interred in the Hale o Keawe, a replica of which, complete with fierce kii statues, stands to this day. The puuhonua is still considered holy ground by many Native Hawaiians—and in modern times, an occasional Hawaiian activist takes shelter here against the authorities.

The park presents ancient sites in as close to their original condition as you are likely to find anywhere. We encountered National Park Service Ranger Charles Grace, dressed like his ancestors in a

malo (traditional men’s loinscloth) and carving kii for the park. Grace works in the old manner (not quite, he uses metal tools, which didn’t appear until after Cook). “Young people, they don’t have the patience to work months on something anymore,” he says. “It’s hard, but it’s the right way.”

His brother, he notes, is up at Keauhou, patiently carving kii for the newly restored Keeku heiau there, which will soon be even more authentic with its own battlement of ancient kii.

This was once a fierce and wild place. Just across the bay from the park, Kamehameha I won his first great victory at the Battle of Mokuohai. A shark-tooth dagger ended the life of the Big Island chief who was his greatest rival. During the battle, women and children from both sides fled to the City of Refuge for safety.

After the fighting, many of the warriors from the defeated side swam feverishly across the bay to sanctuary here in the puuhonua—secure in Hawaiian traditions that no one knew would soon be swept away by the course of history.