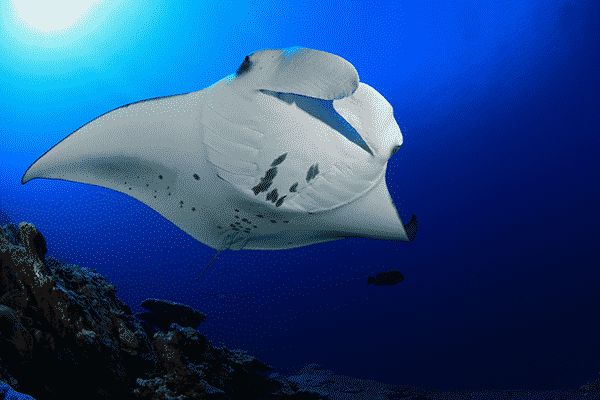

Our eco-friendly manta ray and snorkel tours offer one of the best tourist experiences on the Big Island. Michael Greshko for National Geographic on the migration habits of the majestic manta ray.

Scientists have found that oceanic manta rays (Manta birostris) usually live their lives in distinct, local subpopulations, changing how conservationists approach protecting the mysterious fish species.

It turns out that humans aren’t the only species weary of long commutes: A new study reveals that manta rays living in the open ocean prefer staying close to home, rather than migrating over long distances.

The findings, based on years of tracking data, tissue samples, and genetic tests, are the latest to overturn long-held ideas about how the giant, mysterious fish eke out a living—and how they should be protected from overfishing.

Bigger than their reef-dwelling relatives, oceanic manta rays (Manta birostris) grow up to 23 feet (7 meters) wide and weigh up to 4,440 pounds (2 metric tons). They filter their food out of the water, snacking on plankton, fish eggs, krill, and occasionally small fish.

Scientists had long thought that oceanic manta rays migrated thousands of miles around the world to follow shifts in the distribution of their food, similar to the movements of other pelagic, or open-ocean, filter feeders such as baleen whales and whale sharks. Previous studies had even documented individual manta rays traveling hundreds of miles at a time.

“We sort of assumed that they were behaving the same way that other large pelagic species do,” says lead author Josh Stewart, a Ph.D. student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. (Stewart’s work was supported in part by the National Geographic Society/Waitt Grants Program.)

But when Stewart and his colleagues used satellite tags to track 18 manta rays at sites in Mexico and Indonesia for up to six months at a time, they found that manta rays were far from long-distance travelers.

On the contrary, they seemed to prefer a short commute.

The tracking data, published Monday in Biological Conservation, indicated that 95 percent of the time, the manta rays at each site stayed in patches of ocean as small as 140 miles (220 kilometers) across and rarely if ever journeyed outside of them.

In Mexico, for instance, mantas tagged near the Revillagigedo Islands—some 373 miles (600 kilometers) off the country’s Pacific coast—never ventured to the coast, and vice versa.

And when the researchers analyzed tiny muscle samples taken from each tagged manta, they found that the mantas in each location had their own genetic and dietary quirks—shooting down the idea that they regularly traveled and mixed with other populations.

“The results are surprising, especially when considering the mantas off Mexico [and] that the overlap between populations isn’t greater,” says Lydie Couturier, a manta expert at France’s Institut Universitaire Européen de la Mer who wasn’t involved with the study.

Protecting the Gentle Giants

Couturier and Stewart say that the findings have major conservation implications for the species, which is currently listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Manta rays are frequently caught as bycatch and are hunted for their gill plates, a popular ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine.

“If you had a fishery that was drawing from the entire population of Indo-Pacific mantas, then [killing] 10 [to] a hundred mantas a year wouldn’t be a huge number, necessarily,” says Stewart. “But if there are these very local, isolated subpopulations, then you’re talking about removing half of the population in a year.”

Paradoxically, that vulnerability may also bring benefits, by intensifying pressure on regional and local governments to conserve mantas on their own.

Currently, oceanic mantas are protected mainly by two international agreements: CITES, which forbids the international trade of wild manta-based products, and the Convention on Migratory Species, which provides a framework for international agreements on manta conservation.

Both treaties have had their successes, says Stewart, but they are difficult to enforce because of the large numbers of countries involved. Local and regional agreements, however, have fewer stakeholders—speeding up the adoption of conservation protections.

“If we can see that there are discrete subpopulations within Mexican waters, that would enable Mexico as one country to protect breeding, sustainable pockets of these animals themselves,” says Guy Stevens, the founder and chief executive of the conservation nonprofit Manta Trust, which supported the research. “That doesn’t require any international agreement. They can get on with it [and] protect these animals.”

This kind of local-first strategy already has borne fruit. In 2013, conservation groups, including the Manta Trust, worked with the local government of Raja Ampat, an archipelago in northeast Indonesia, to create Indonesia’s first shark and manta ray sanctuary.

But more work remains, especially to figure out how manta rays survive by staying in one place while their similarly filter-feeding peers opt for wider travels.

Another Stewart-authored study, published in May in Zoology, suggests that manta rays instead travel vertically, swimming into deeper waters periodically to make their diets more varied. That hunch won’t be confirmed until researchers have video of the mantas’ feeding behaviors—a project National Geographic is currently supporting with its Crittercam initiative.